LabManager Features ASSURE Lead University, Mississippi State University’s Research

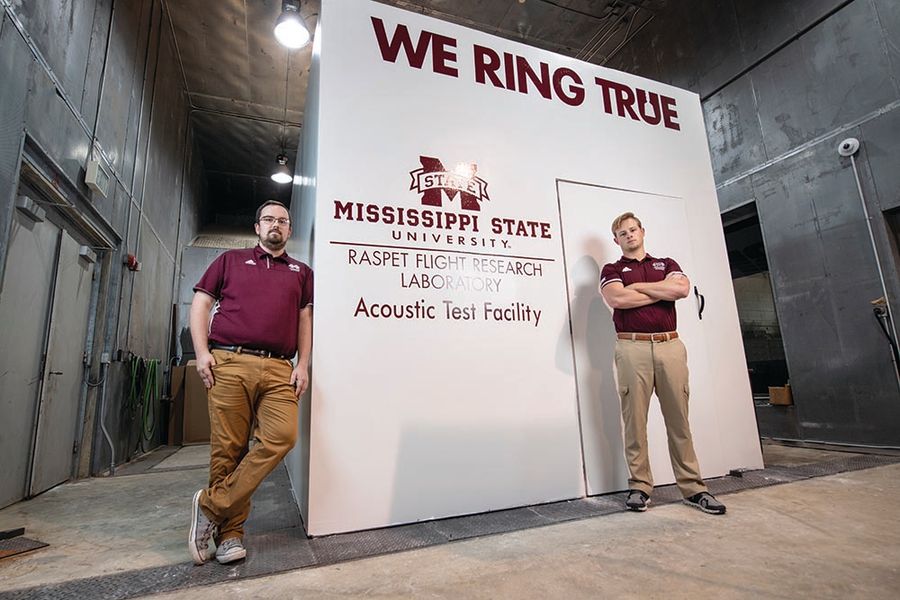

Engineers at Mississippi State University’s (MSU) Raspet Flight Research Laboratory have constructed a special interior room to conduct research on making quieter unmanned aircraft systems. The lab, located in Starkville, MS, is the leading academic research center in the US that is dedicated entirely to the advancement of unmanned aircraft systems (also known as UAS, or more commonly known as drones).

In addition to federal agencies, the lab collaborates with commercial industries regarding composite materials research. One such collaboration with Southern Company, an energy company with subsidiary power companies across the southern US, seeks to use larger, more sophisticated UAS to map out critical infrastructure, examine weather-related damage, and perform routine utility inspections.

Creating an ultra-quiet room

The acoustic anechoic chamber is the quietest space on campus, despite being located adjacent to a local airport runway. The facility was designed and built by Raspet’s engineers, working in collaboration with expert faculty within MSU’s Bagley College of Engineering. The lab is also a collaboration with the US Department of Defense, which is seeking to quiet UAS. The goal of the research is to one day allow UAS to fly cooler, quieter, and more efficiently, without sacrificing their performance.

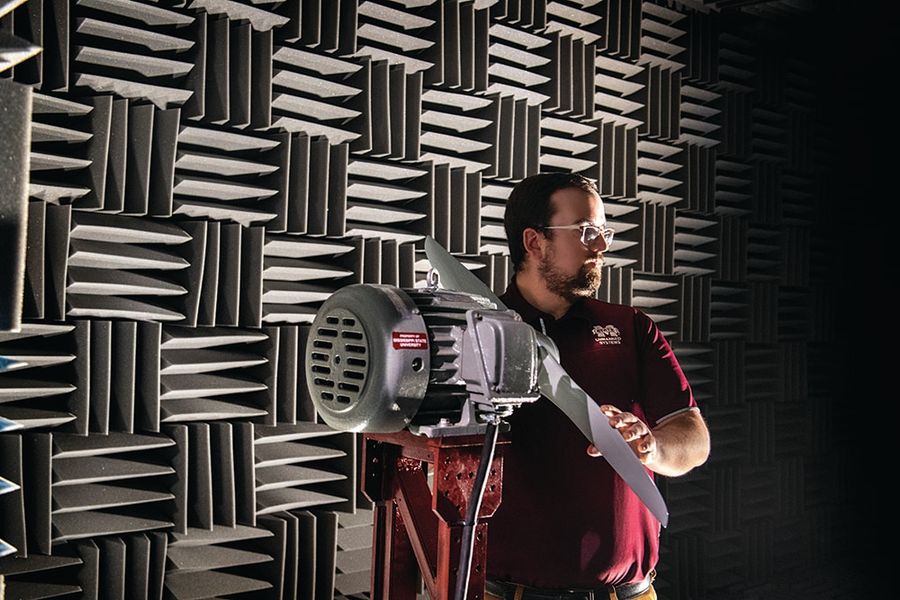

“A room within a room, our acoustic anechoic chamber absorbs sound reflections from within while providing insulation from exterior noise. Equipped with best-in-class microphones, this environment enables us to precisely measure and record sounds,” says Tom Brooks, director of the Raspet Flight Research Laboratory. “For example, we presently have an electric motor mounted to a test stand at one end of the chamber. We can mount various propellers to the motor and turn them at different revolutions per minute (RPMs), which allows engineers to evaluate the noise associated with the propeller while independent of the mechanical noise source that would be attributed to a reciprocating engine. Operators outside the chamber control the motor, and the microphones are linked to computers where specialized software captures the data needed for our research projects. Through this setup, we can accurately and precisely measure sounds generated by the rotating propellers.”

The chamber, which is designed and built to international standards, has an ambient noise floor measuring 16.5 dBA—this level is quieter than a whisper and is barely more audible than a person breathing at a normal rate. The 10 ft. by 18 ft. by 10 ft. acoustic anechoic chamber is entirely covered by dozens of eight-inch-deep polyurethane foam wedges. It is designed to absorb sound waves emanating from within, and halts the waves from bouncing within the room while simultaneously providing insulation from exterior noise. The researchers are therefore able to precisely measure the exact sounds on which they want to focus.

“Entering these chambers can cause a bit of a sensory celebration,” says Brooks, describing the polyurethane foam wedges which line every surface. “The shape and positioning of the foam wedges create a visually interesting experience—a sort of kaleidoscopic effect. The extent of the silence the room creates causes some to express feelings of disorientation when they enter.”

Current work

The lab is currently working on a project involving two groups of UAS, known as Group 2 (weighing between 21 and 55 pounds, and typically operating at less than 3,500 feet) and Group 3 (weighing between 55 and 1,320 pounds and flying at less than 18,000 feet). The research team will measure noise produced by propellers, which have been reconfigured for the project, with four or five blades rather than the usual two, and which rotate at fewer RPMs in order to reduce noise. The goal is to discover which propellers create the same (or acceptably equivalent) thrusts at a potentially lower RPM—this may lead to propeller modifications in real UAS to achieve quieter flights. The tests will be run both inside the chamber as well as later during actual test flights.

There is also important research that takes place outside of the acoustic anechoic chamber—this includes equipping aircraft with newly designed hydrogen fuel-cell powered electric motors, along with tuning exhaust systems and altering drive systems aimed at reducing noise. Measures to dampen heat are also taken. The overall project also involves measures to dampen heat.

“All this work, whether performed inside or outside the chamber, is about creating the ability to fly undetected at lower altitudes. If you can fly undetected at lower altitudes, your sensor resolution is higher and you can pick out better details,” says Brooks. “We, alone with our research partners, are ensuring that the reconfigured airplanes remain mission-capable.”

The main challenge when dealing with testing unmanned aircraft in an acoustic anechoic chamber, says Brooks, is scalability. “The traditional technical solutions generally applied to traditional manned aircraft (or larger unmanned aircraft) simply do not scale to smaller air vehicles. Size, weight, and power challenges always exist, and finding solutions that avoid payload or flight endurance penalties can be challenging. This is what makes the unmanned aircraft field so engaging,” he says.

Another engaging part of working in the Raspet Flight Lab is knowing that those who created the lab are closely involved with it, and the university as a whole. “My favorite aspect of this lab is the satisfaction that comes from our in-house team having designed and built it. In partnership with expert faculty in MSU’s Bagley College of Engineering, our team conceptualized, then developed and matured a capability that did not previously exist at MSU. That’s quite rewarding. We enjoy working with students, and labs like this one always seem to spark a lot of interest. It’s eye-catching and different from what our students have previously seen,” says Brooks.